Staffing Management

Getting Schooled on Diversity

By Andie Burjek, Grey Litaker

Nov. 5, 2019

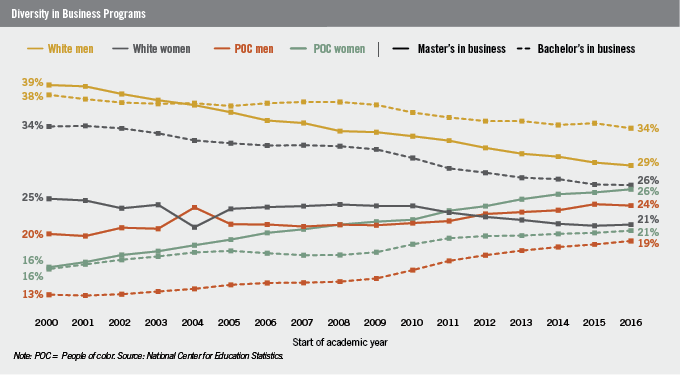

As the 21st century dawned, enrollment in university MBA programs was a virtual rainbow of diversity. In the early 2000s, MBA graduates were comprised of 36.2 percent people of color and 40.7 percent of grads were women, while 39.1 percent were white males.

At about the same time, chief executive roles were predominately occupied by males, most of whom were white. More than 89 percent of white men and women occupied the chief executive’s chair as of 2005, with 76 percent of those executives being male.

Considering that getting an MBA is generally a key element to a career path leading to the C-suite, the following years should have seen a succession of female and minority executives ascending to leadership roles.

That doesn’t appear to be the case, according to the research department of Human Capital Media, Workforce’s parent company, which compiled data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Center for Education Statistics annual digest. The data show that diversity in the C-suite has not kept up with MBA graduation patterns of the past two decades.

In fact, little appears to have changed since that graduating class of 2000-01. As of 2018, the most recent data available, the numbers have barely budged, with 73.1 percent of chief executives who are men and 89.5 percent who are white.

Yet mounting evidence points to diverse leadership as an economic driver. “Delivering Through Diversity,” a 2018 study by consulting firm McKinsey & Co., found that gender-diverse companies are 21 percent more likely to outperform their non-gender-diverse peers financially, and that the number for ethnic and cultural diversity is 30 percent.

A September 2019 report released by global communications company Weber Shandwick meanwhile found that when diversity is closely aligned with the overall business strategy, companies see a positive impact on reputation, employee retention and financial success. Among organizations that align their diversity strategy with their business strategy, 66 percent of diversity leaders said that D&I is an important driver of financial performance, the study found.

Even so, government data show that a diversity shortage continues to afflict executive level positions.

With research showing that the executive pipeline has been filled with diverse MBA graduates for two decades, it begs the question of where did these candidates go? And if diverse leadership indeed pushes the financial needle, as the evidence shows, then why has corporate America turned its back on this pipeline of ready-made diverse executives?

“In the 1960s, we had begun to see change. The doors were finally open to people who had historically been left out,” said Pamela Newkirk, a professor of journalism at New York University whose new book “Diversity, Inc.” takes a deep look into how workplace diversity efforts have done little to bring equality into America’s major industries and institutions.

The 1960s specifically saw efforts like affirmative action implemented to make up for the legacy of slavery and the legal discrimination that followed the end of slavery, she said. These efforts were beginning to see positive results but ultimately saw adverse responses from people who challenged affirmative action with claims of reverse discrimination.

By the 1970s, diversity numbers were barely seeing change in fields from corporate America to higher education to major media.

“Society has not been able to come to terms with ways to address this that don’t trigger the kind of backlash we’ve seen time again,” she said.

With research showing that the executive pipeline has been filled with diverse MBA graduates for two decades, it begs the question of where did these candidates go?

Rethinking the Talent Pool

Most leaders don’t know what it means to lead diversity, said Courtney Hamilton, managing director at The Miles Group, a management consulting company based in New York. Consciously or not, they may lean toward conformity and then lose the wider talent pool along the way.

Building a diverse pipeline for organizational leadership comes down to what companies are doing in hiring and promotions, she said.

Many companies try to “reverse engineer” diversity in their teams when a position opens up, she said. While it’s not bad to think about diversity when looking to hire, that is more of a reactive than a proactive strategy.

“What people miss in building a diverse pipeline and leading inclusively [is that it] needs to be front and center for organizations every single day. There is no Band-Aid. If you want that pipeline of talent, it needs to be a value and priority,” Hamilton said.

Kevin Groves, associate professor of management at Pepperdine University’s Graziadio Business School, said that many organizations fall into the trap of allowing boards or management teams to follow their intuition to pick new members of the leadership team. This intuitive judgment leads to a less diverse talent pool.

There is a way around this trap, he said: a standardized review process that is not exclusively based on the board’s judgment. This formalized talent review should be parallel to but separate from the annual performance review.

It’s a tough hurdle to overcome, Groves stressed. It comes naturally to employers to believe that they know their talent best and can be reliant on their own judgment for these big decisions. This isn’t to say that the executive team should ignore their judgment completely, but the starting point for the candidate pool should be something standardized and data-driven rather than intuitive.

What’s especially helpful in diversity hiring is casting a wide net and “not assuming that when it comes to placement of key executive roles, the only place that can come from is an heir apparent,” Groves said.

Deloitte is one organization that has worked to expand its talent pool. While the professional services industry has historically looked toward a small set of specific universities to recruit from, Deloitte is making room for those schools previously overlooked like state schools and historically black colleges, said Terri Cooper, the firm’s chief inclusion officer.

Opening the search to a wider range of people allows for a more diverse group of candidates. But the benefits go beyond that, Cooper said. Looking toward the future of work, candidates with specific skills — rather than candidates with degrees from a specific school — are likely to be the right fit for a role.

It’s important to “make sure that your aperture isn’t so specific that it’s preventing the opportunity to bring that greater diversity into the fray,” Cooper said.

Diversifying the C-Suite

Rising to a C-suite position is the culmination of many experiences that start much earlier in a person’s career, like the opportunity to rise through the ranks in management positions. Such management roles are not particularly diversity-friendly.

BLS data show that 60 percent of those in management positions are men versus 40 percent who are women, and 77.9 percent of those in management are white while the numbers are much smaller for black, Asian and Latinx populations. Moving to positions higher up the corporate ladder, the gap becomes wider, with a chief executive population that is only 26.9 percent women and 14.8 percent people of color.

There’s more opportunity to tackle diversity at the management level than the executive level because the population is larger and less competitive. While management positions make up 5.3 percent of the total workforce, chief executives only make up 0.1 percent, according to 2018 BLS data.

Studies show that people in underrepresented groups face many opportunity roadblocks such as fewer mentorship or sponsorship opportunities and fewer opportunities for growth within the organization, said Molly Brennan, founding partner and executive vice president of Boston-based executive search firm Koya Leadership Partners.

“This idea that there’s not a lot of qualified candidates [from] underrepresented groups out there is a false one,” she said. “There’s a whole host of diverse, qualified people who are ready, willing and able to take on leadership roles.”

Cooper said recruiting diverse talent is not the biggest challenge most organizations have. Rather, it’s advancing them within the organization to higher positions.

A key component to ensuring that talent advances is that companies must be more intentional about what an inclusive leader is and how the organization can hold leaders accountable to supporting diversity. This doesn’t mean just the most senior level of leadership but anyone who is in charge of managing people.

Deloitte relies on six components of an inclusive leader, Cooper said. They include a personal commitment to diversity, creating a work environment that allows people to identify bad behavior and being curious about others’ backgrounds and heritages.

The fundamental component here is that leaders make sure individuals can be their most authentic self at work, she said. If people are experiencing bias, it has a negative effect on their productivity, happiness, confidence and well-being, she added.

“Ultimately, if you’re experiencing that, of course you’re going to leave the organization. You’re going to look to find somewhere else where you feel you’re accepted for who you are,” she said.

There are many ways in which organizations can hold leaders accountable, Cooper said. They can set specific diversity goals for leaders and measure their success reaching those goals. They can also have leaders share specifically what initiatives they have taken to create an inclusive environment and what their recent experiences have been on mentoring or sponsoring people who don’t look, think or sound like them.

Further, other people should be able to comment on their leaders, Cooper said. Deloitte holds an expansive talent survey annually, and eight to 10 questions are specifically geared toward how inclusive of a culture they experience. Questions include: Do you feel like you’re being professionally developed? And do you feel as if you belong on your team?

Dissecting this talent data allows Deloitte to see aggregate data at a particular client site, for example, and identify the lead partner there. They can help show if this partner is truly creating an inclusive work environment for their employees.

Deloitte is careful with this data so that no one can be identified based on their answers, and the information “enables us to determine where we need to focus to move the needle,” Cooper said.

A Partnership Between D&I and Recruiting

Focusing on the relationship between the diversity and recruiting teams is key to Deloitte’s strategy, Cooper said. Deloitte spends a lot of time looking at available candidates and also expanding their awareness of diversity beyond gender and race. How is the company making sure that it considers talent from different socioeconomic backgrounds or neurodiverse candidates, for example.

What’s critical from the recruiters is that they’re aware of their biases, Cooper said. Her department pushed unconscious bias training for the recruiting team, and there has been positive feedback to this.

Chevron also has recruiters participate in bias training, said Lee Jourdan, the energy giant’s chief diversity officer. It’s part of the influence that employee resource groups have had on recruiting.

Such groups have been a part of Chevron for 20 years, and they work with hiring teams by helping them communicate with a broader range of candidates and lead interviews. There are 63 chapters in 12 countries, and the groups represented include women, people of different races and ethnicities, people with disabilities and those from indigenous tribes.

Through bias training and their relationship with the resource groups, recruiters work on mitigating their biases. Jourdan said they have removed the requirement that a candidate has a specific number of years of experience to get a role. This can exclude people who have not been given the opportunity in the past to gain certain experience, he added.

Employee groups have also helped the global company consider different types of diversity per region or country, Jourdan said. For example, there are three major tribes in Nigeria, and people may be marginalized if they are not a part of one of these tribes, he said. Chevron’s diversity efforts there could partly be geared toward this group.

Making Diversity a Business Imperative

At executive search firm Koya, which mostly recruits for leadership positions at nonprofits, clients increasingly are expecting and requiring a diverse pool of talent, Brennan said. Their focus on making diversity a priority has seen promising results. Forty percent of its placed candidates are people of color, she said.

This number is much higher than the general leadership population. Brennan believes this is because they purposely and consciously set out to make this number high. It’s both what the client and the search firm want.

Aspirational diversity goals help Chevron continually create a more even playing field, Jourdan said. Rather than having specific diversity targets for individuals of underrepresented groups, he believes that aspirational numbers, whether or not they are reached in a given year, help the organization take on certain behaviors and move in a positive direction.

One place to look for these aspirational numbers is the demographics of individuals graduating from business school, Jourdan said.

“We believe that [diversity targets] drive the wrong behavior. We’re vocal about the fact that we don’t do those,” Jourdan said. Rather, he said that Chevron holds leaders accountable to move toward improving numbers to achieve the aspirational goals.

Most importantly, it takes leadership and intention for diversity to work, author Newkirk said.

She stressed something that Columbia University President Lee Bollinger said in an interview for her book. There must be a sense of justice, especially given the history of slavery and discrimination in the U.S.

“This is also an issue of justice. Without that mindset many diversity initiatives won’t really work,” Newkirk said.

Schedule, engage, and pay your staff in one system with Workforce.com.

Recommended

Compliance

Minimum Wage by State (2024)federal law, minimum wage, pay rates, state law, wage law compliance

Staffing Management

4 proven steps for tackling employee absenteeismabsence management, Employee scheduling software, predictive scheduling, shift bid, shift swapping

Time and Attendance

8 proven ways to reduce overtime & labor costs (2023)labor costs, overtime, scheduling, time tracking, work hours