Workplace Culture

Focus on Employee Work Passion, Not Employee Engagement

By Drea Zigarmi, Randy Conley

Mar. 14, 2019

Every day the spirits of millions of people die at the front door of their workplace.

There is an epidemic of workers who are uninterested and disengaged from the work they do, and the cost to the U.S. economy has been pegged at more than $300 billion annually. According to a recent survey from Deloitte, only 20 percent of people say they are truly passionate about their work. Gallup surveys show that nearly 70 percent of the workforce is not engaged, with an estimated 23 million “actively disengaged.” These employees have quit and stayed — they show up for work but do the bare minimum to get by, don’t put in any extra effort to care for customers and are a drain on organizational resources and productivity.

On the trust front, the findings are just as stark. Studies show that 50 percent of employees who distrust their senior leaders are considering leaving the organization, with 62 percent reporting that low trust causes unreasonable levels of stress. According to workplace consultancy Tolero Solutions, 45 percent of employees say lack of trust in leadership is the biggest issue impacting work performance.

Building and sustaining high levels of engagement is a critical competency for today’s leaders. In our technology-fueled, digitally connected world where new products, competitors and business models seem to emerge overnight, one of the few competitive advantages an organization possesses is its people. The level of skill, talent, creativity, innovation and passion in the workforce of an organization can mean the difference between mediocre and exceptional results.

Focusing solely on engagement is not enough to get us there. We must shift the focus from engagement to the creation of a high-trust culture where employees are passionate about their work.

From Employee Engagement to Employee Work Passion

Employee engagement is a broad and complex problem that organizations spend $720 million a year trying to solve, according to a Bersin & Associates report. Yet when it comes to engagement there isn’t even a commonly accepted definition of the term. Descriptions vary widely, with elements that include commitment, goal alignment, enjoyment and performance, to name a few.

We make a few critical distinctions between the concepts of engagement and employee work passion.

First, employee work passion is supported by a theory and model that explain how work passion is formed. We believe employee work passion is better understood by considering the influence of research on social cognition, appraisal theory, job commitment and organizational commitment. Therefore, it is a different and more expansive concept than engagement.

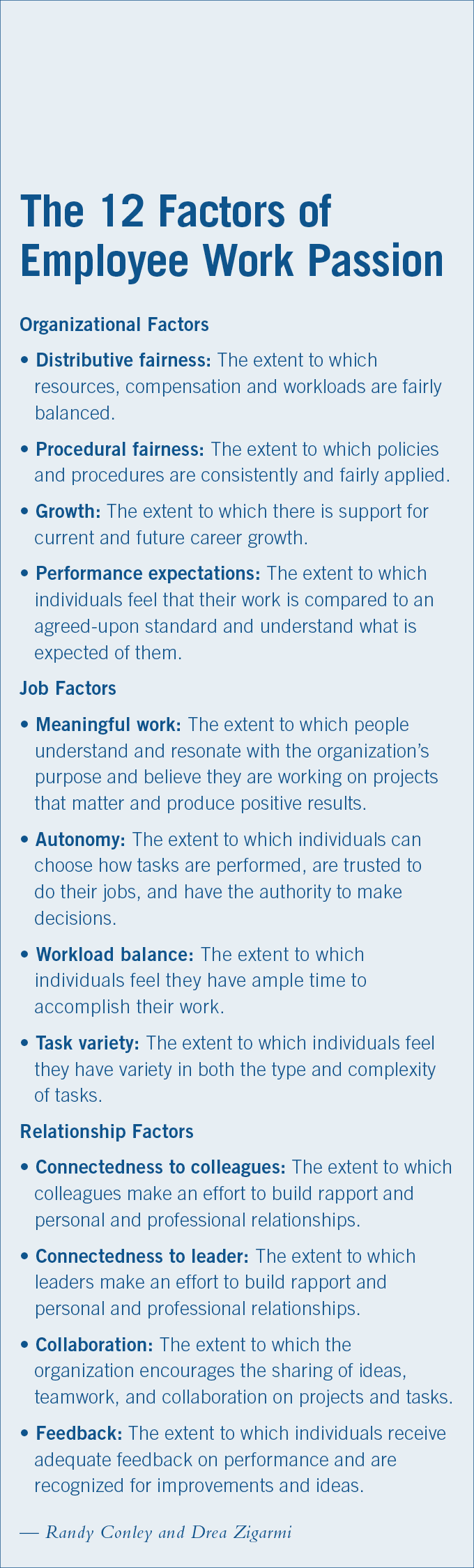

Second, the combination of relationship, organizational, and job factors influence an individual’s level of work passion. Whereas engagement is often linked to job satisfaction, employee work passion considers the cognitive and affective appraisals people make when assessing their environment and the meaning they ascribe to their thoughts and feelings.

Creating Employee Work Passion

To understand how employee work passion occurs, one must consider the process an individual goes through when deciding to employ a specific behavior. As stated earlier, much of the research on engagement does not take the full scope of this process into account. Through deeper exploration of the literature, we began to incorporate significant ideas found in cognitive psychology.

Employee choices are driven by the understanding of how the experience or event being appraised impacts well-being. Since people are meaning-oriented and meaning-creating, they are constantly reacting (cognitively and affectively) to their environment to form judgments (appraisals) about how their well-being is affected by environmental events.

Cognition and affect go hand in hand, happening almost simultaneously, over and over, as individuals make sense of a situation. The conclusions they reach about what is happening, what it means to them, how it will affect them, how they feel about that, what they intend to do, and — finally — what they actually do, are all filtered through the lens of who they are.

The model suggests that the appraisal process begins with an assessment of the organizational, job and relationship factors. During the appraisal process, an employee makes sense of how they feel about the extent to which the 12 factors are present in the work environment.

There are multiple steps in the appraisal process. First, individuals make cognitive (thinking) and affective (feeling) judgments of their environment: What do I think about what’s happening around me and how does it make me feel.

Next, an employee’s passion moderates, or shapes, those appraisals into intended behaviors. Passion can be categorized in two ways: obsessive and harmonious.

Obsessive passion can be described as activity individuals engage in because they “have to,” “must do,” or “needs to,” often to their own detriment (such as addiction, compulsiveness, etc.).

Harmonious passion are those activities that could be described as “gets to,” “wants to,” or “can’t wait to” perform. Harmonious passion is exhibited when people lose themselves in the flow of an activity. The final step of the appraisal process occurs when individuals form conscious intentions to behave in certain ways, as measured through the five intentions. These intentions ultimately lead to either positive or negative job and organizational behaviors.

Trust’s Role in Employee Work Passion

High levels of trust between leaders and employees foster engagement and vitality in an organization’s culture. The 2017 “Employee Job Satisfaction and Engagement” report from the Society for Human Resource Management showed the top two contributors to employee satisfaction were respectful treatment of all employees at all levels (65 percent) and trust between employees and senior management (61 percent).

Studies have shown that committed and engaged employees who trust their leaders perform 20 percent better and are 87 percent less likely to leave the organization, and that high-trust organizations experience 50 percent less turnover than low-trust organizations. Despite the amount of evidence pointing to the personal and organizational benefits of having a high-trust culture, however, many organizations lack an intentional approach to building trust.

Trust doesn’t come easy and it doesn’t happen by accident. One challenge in building trust is that it is based on perceptions — one person’s idea of what trust looks like in a relationship can be different from another’s. So, it is critically important for leaders and organizations to establish a shared definition for and understanding of trust.

A leader’s trustworthiness is composed of four elements that we’ve captured in the ABCD Trust Model. Leaders are trustworthy when they are:

Able: Able leaders have the expertise, training, and qualifications to perform well in their roles. They also have a track record of success as they demonstrate the ability to consistently achieve goals. Able leaders are skilled at facilitating work getting done in the organization. They develop credible project plans, systems and processes that help team members accomplish their goals.

Believable: A believable leader acts with integrity by dealing with people in an honest fashion; e.g., keeping promises, not lying or stretching the truth, not gossiping, etc. Believable leaders have a clear set of values. They communicate these values to their direct reports and use them consistently as a model for their behavior: They walk the talk. Finally, treating people fairly and equitably is a key characteristic of a believable leader. They are attuned to the dynamics of distributive and procedural fairness (see sidebar) and uphold those principles in the workplace.

Connected: Connected leaders show care and concern for people, which builds trust and helps create an engaging work environment. Leaders can create a sense of connection by openly sharing information about themselves, the organization and by trusting employees to use that information responsibly. Taking an interest in people as individuals, not nameless workers, shows that these leaders value and respect their team members. Recognition is a vital component of being a connected leader and praising and rewarding employees’ contributions builds trust and goodwill.

Dependable: Being dependable and maintaining reliability is the fourth element of trustworthiness. One of the quickest ways leaders erode trust is by not following through on commitments. Conversely, leaders who do what they say they are going to do earn a reputation of being consistent and trustworthy. Maintaining reliability requires leaders to be organized so that they can follow through on commitments, be on time for appointments and meetings, and get back to people in a timely fashion. Dependable leaders also hold themselves and others accountable for following through on commitments and taking responsibility for their work.

The trust one places in a leader comes in two forms: cognitive trust and affective trust. In relation to the ABCD Trust Model, cognitive trust is based on the confidence one has that a leader is able and dependable. This is trust from the head, where rational thought and experience rule. Affective trust, or trust from the heart, is formed by emotional closeness, empathy or friendship. It aligns with “Believable” and “Connected” in the ABCD Trust Model. Our research has shown a large degree of correlation between trust (cognitive and affective combined) and all five work intentions.

Next Step for Leaders

When looking to create a culture where trust flourishes and employees are passionately committed to their work, leaders should examine how the ABCDs of trust are modeled in everyday behaviors, and the extent to which the 12 factors of employee work passion are present. Leaders should ask themselves the following questions:

Does our culture allow individuals to find meaning in their work, their roles and our organization’s purpose?

Are policies, procedures, benefits and compensation transparent and equitably applied to all?

Does our organization provide growth opportunities? Do our feedback mechanisms allow individuals to improve?

Do individuals understand what is expected of them and have a reasonable amount of autonomy when engaging in projects and tasks? Does our organization provide opportunities for individuals to collaborate with others?

Are job roles balanced and reasonable, with enough variety to challenge people perform at optimal levels?

Does our organization have an intentional approach to building trust? And do leaders exhibit the ABCDs of trust in their relationships?

While it may seem daunting to address and incorporate the ABCDs of trust and the 12 factors of employee work passion into the workplace, organizations that do so will be rewarded by trustworthy and passionate employees dedicated to creating devoted customers, achieving sustainable growth and increasing profits for the organization.

Schedule, engage, and pay your staff in one system with Workforce.com.

Recommended

Compliance

Minimum Wage by State (2024)federal law, minimum wage, pay rates, state law, wage law compliance

Staffing Management

4 proven steps for tackling employee absenteeismabsence management, Employee scheduling software, predictive scheduling, shift bid, shift swapping

Time and Attendance

8 proven ways to reduce overtime & labor costs (2023)labor costs, overtime, scheduling, time tracking, work hours